Field Trip to Western Australia 2023

Published on

11/03/2023

11/03/2023

Written by

ISABELLA ONG

ISABELLA ONG

Murchison Widefield Array. Photo credit: Marianne Annereau, 2015

Murchison Widefield Array. Photo credit: Marianne Annereau, 2015

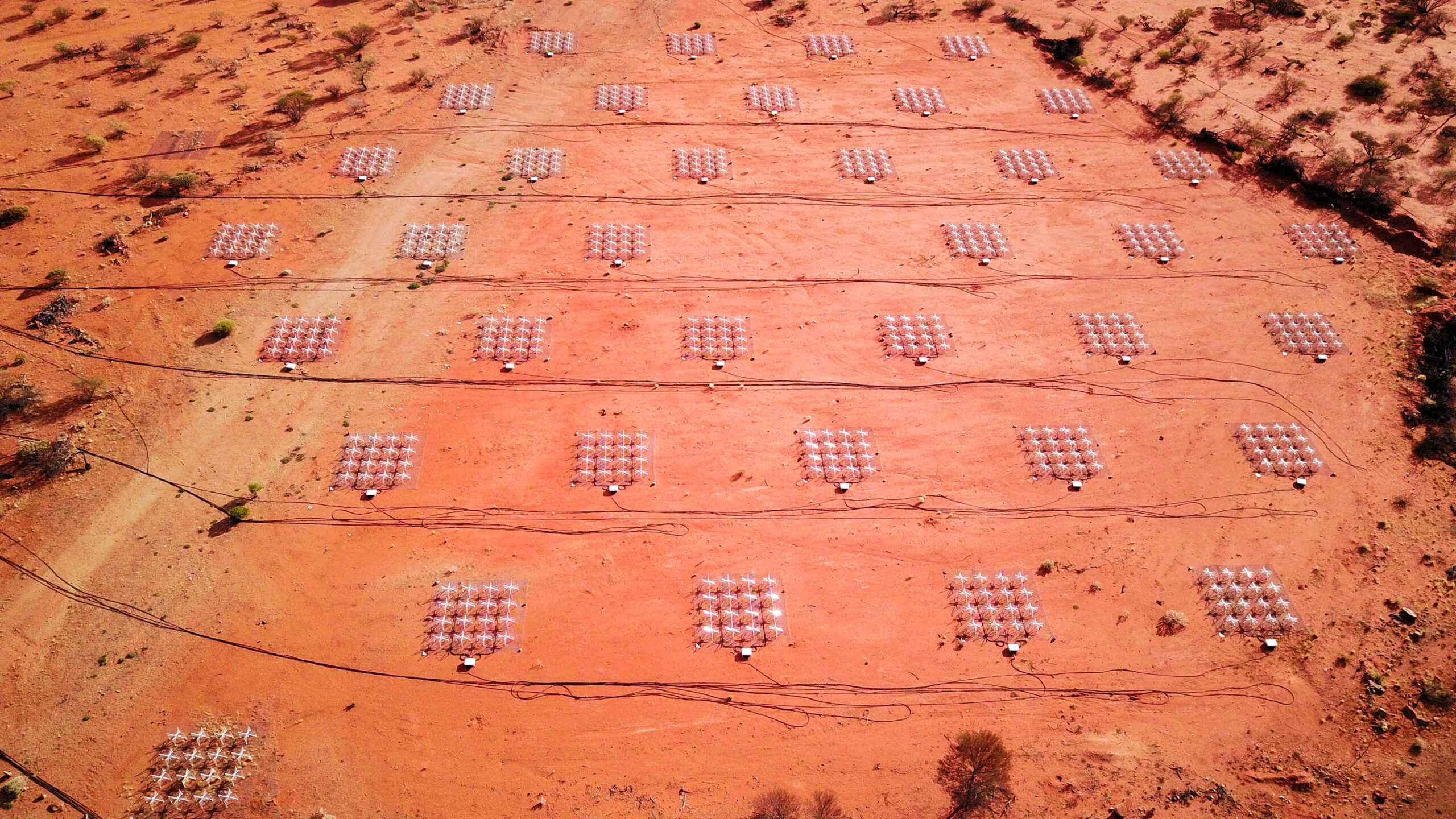

View of the Murchison Widefield Array from above. Photo from: MWA’s website

Zadko Observatory. Photo credit: University of Western Australia

As part of the research fieldwork for this project, I will be taking a trip to Western Australia in March 2023 to visit both the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) and Zadko Observatory.

The first part of the trip will be hosted by Professor Steven Tingay of Curtin University and the MWA, where we will travel up to Murchison via Geraldton to tour the radar facility. The MWA is a low-frequency radio array, operating in the frequency range of 70–300 MHz, with the capability of observing a very large area of the sky.

Among the many scientific objectives for the radio telescope array, one goal is to detect and track space debris, using radio broadcast stations as “non-cooperative transmitters”1. Researchers at the MWA are exploring the possibility of mapping out the positions of space debris by reading the FM broadcasts that are propagated into space and reflected off the debris in Earth orbit, which are then picked up by the MWA. I love the term ‘non-cooperative transmitters’ and the fact that the radio array are listening out for the reflected songs that are being played by radio stations around the world—all the love ballads, pop songs and dance music bouncing of the thousands of objects orbiting Earth.

The indigenous name of the telescope alludes to its listening capabilities. The Wajarri-Yamaji people are the traditional owners and native title holders of the site, and the Wajarri name for the MWA telescope is Gurlgamarnu (pronounced ‘Golga-mahn’), which means “the ear that listens to the sky.”

The site in Murchison is located far away from towns and cities as it requires an area that is protected from any interference. The entire site is a radio-quiet zone and I look forward to being completely disconnected while enjoying one of the darkest, most pristine night sky in the world.

A caution to switch off all radio emitting devices when in the MWA site in one of the preparatory emails.

The second half of the field trip is hosted by the University of Western Australia (UWA. The trip itinerary includes a visit to the Gingin Gravity Precint, 70km north of Perth where the Zadko Observatory, a 1.0 metre f/4 robotic telescope, is located.

Since 2004, UWA researchers have been collaborating with French Astronomers and CNES (The French Space Agency) to observe and study satellites and debris in geostationary orbits. This research has led French astronomers to develop new techniques that allow them to track space debris down to centimetre-scale lengths. Currently, only objects larger than 10 cm are tracked and catalogued in the satellite datebases.

In preparing for the trip to these radar and observatory sites, I often come back to this idea captured by Rajji Desai in her essay “Afterlives of Orbital Infrastructures”, where she writes about the ‘false externalisation’ of satellite systems:

“Despite their operational lives occurring in a place more or less external to the Earth, these ostensibly externalised toxic wastes are ultimately subject to important processes of (re-)internalisation back here on Earth. Crucially, these processes have dire consequences for Earth’s environments — whether built or unbuilt, human or non-human.”2

Though parted from Earth and adrift in space, these debris objects are still tethered to our planet and hold a geographic and terrestrial affiliation. Dedicated facilities have been constructed for the express purpose of monitoring space debris, including the two sites that I will have the opportunity to explore—the ears and eyes of our planet, listening and looking out for these satellites. These ground stations, to some extent, are the connections we preserve to these aloof and alienated artefacts in orbit.

1 Tingay, S.J. and Kaplan, D.L. and McKinley, B. and Briggs, F. and Wayth, R.B. and Hurley-Walker, N. and Kennewell, J. 2013. On the detection and tracking of space debris using the Murchison Widefield Array. I. Simulations and test observations demonstrate feasibility. Astronomical Journal. 146 (103).

2 Desai, R. 2019. Afterlives of Orbital Infrastructures: From the Earth’s High Orbits to its High Seas.